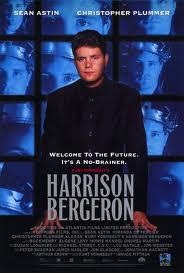

In case you are not familiar with it, Harrison Bergeron is a short story by Kurt Vonnegut, set in a futuristic dystoptia where everyone in the world is finally equal in all ways. No one is smarter or stronger or more talented than anyone else and this miracle of equality is brought about by bags of bird-shot. Those who are judged to be superior in anyway are required by law to wear bags loaded with lead weights, or fixed with headphones which emit ear-splitting sounds, or wear hideous masks to hide beauty. And the smartest and strongest and most beautiful of all the inhabitants of this brave new world is Harrison, the fourteen year old son of George and Hazel, and an escaped convict. It was a story I taught to my sixth grade students a good number of years ago and like many stories, certain lines were implanted forever in my brain.

In case you are not familiar with it, Harrison Bergeron is a short story by Kurt Vonnegut, set in a futuristic dystoptia where everyone in the world is finally equal in all ways. No one is smarter or stronger or more talented than anyone else and this miracle of equality is brought about by bags of bird-shot. Those who are judged to be superior in anyway are required by law to wear bags loaded with lead weights, or fixed with headphones which emit ear-splitting sounds, or wear hideous masks to hide beauty. And the smartest and strongest and most beautiful of all the inhabitants of this brave new world is Harrison, the fourteen year old son of George and Hazel, and an escaped convict. It was a story I taught to my sixth grade students a good number of years ago and like many stories, certain lines were implanted forever in my brain.THE YEAR WAS 2081, and everybody was finally equal (Vonnegut, 1961). And as good as that might sound, the equality Vonnegut describes is not at all the world I want for my children, particularly for my autistic son. George Bergeron, Harrison's father, is forced to wear a "handicap" of 47 pounds of bird-shot padlocked around his neck because he has been judged to have a superior intellect. And as the little pieces of bird-shot rolled across my floor, an image of my son when he was young and struggling in school came to my mind. He did not need bags of bird-shot as a handicap.

Equality does not exist. There will always be those who are better at some things, smarter at some things, more athletic at some things. Yes, we were all created equal and our rights as citizens guarantee us the same liberties as others. But we are all unique, little pieces of bird-shot unlike any other. Equality, as Vonnegut points out, does not solve everything:

Some things about living still weren't quite right, though. April for instance, still drove people crazy by not being springtime. And it was in that clammy month that the H-G men took George and Hazel Bergeron's fourteen year-old son, Harrison, away (Vonnegut, 1961). Harrison makes his way to a television studio where a ballet program is being broadcast. George and Hazel are in their home, watching the show, when Harrison bursts into the scene. But their handicaps keep them from being concerned with their son.

I am always concerned with mine. Allen, quite in keeping with someone who has Asperger's Syndrome-- the highest functioning form on the autism spectrum-- was more concerned about his vest than my floor and the bouncing bird-shot. While Bonnie and Jared did their best to clean up, Allen wanted to know what was to be done with his vest. My mind still occupied with the final scenes of Vonnegut's story, where Harrison has ripped off his handicaps and is dancing with the most beautiful ballerina without her hideous mask, I suggested duck tape, our usual go-to for household emergencies.

"NO!" he loudly declared. "It will ruin the vest. I need you to sew it. That's what I need!"

I tried to be patient. Really. "I can't sew it," I explained. "My sewing machine can't handle fabric that thick."

"Then sew it by hand," he stubbornly insisted. I shook my head. "The material's too tough for that. But maybe we could put the pellets in a new pocket and cut off the old one."

"NO!" Allen shouted. "You are not being helpful." He pounded up the stairs to his room, the vest still oozing bird-shot. Carefully, we picked it up and placed it in a large plastic bag. I heard Allen's door slam.

"NO!" Allen shouted. "You are not being helpful." He pounded up the stairs to his room, the vest still oozing bird-shot. Carefully, we picked it up and placed it in a large plastic bag. I heard Allen's door slam."He'll be back," I told the family. We swept up as many of the pesky pellets as we could find. I would, I was quite sure, be picking them up for a long, long time. They would hide in cracks and crevices of the floor, the cushions of the couch, the seams of the baseboards. We got out Scattergories, our go-to family game, and began to play a very unequal game. Some of us were better at certain categories than others. Unlike Harrison and George, we did not need ear radios with high pitched screeches and bags of weight strapped to us. We were, all of us, handicapped in our own ways. Not equal. Not by a long shot.

Eventually , as predicted, Allen came back downstairs. He dragged the vacuum cleaner with him and dutifully set to work on the couch and the floor. Then he murmured a brief apology for his actions and joined us for what proved to be a riotous game complete with the laughter that is bound to happen when people who have different talents and different skills get together. In Vonnegut's world the game would have ended in a tie; in this one, Jared was the clear winner.

It was the next day that Allen came to me and offered another apology. "I said you weren't being helpful," he said. "And I know you were trying to be. So, thanks. I was just worried about my vest."

"I know," I said and gave him a hug. "We've all got things that bother us."

I am sorry to tell you that Vonnegut's tale ends in tragedy. While Harrison and the lovely ballerina dance for a while and make the audience awe at their combined beauty, they are both ultimately shot and killed. In 2081, equality is more important than humanity. George and Hazel, equal but deficit, do not even mourn his passing.

Allen, God bless him, is different than his brother and sister. He is different than me or his dad. He has, as we all do, his own bags of bird-shot, his own handicaps. He also has his own talents. As I continue to parent this now-adult through the many nuances of autism, I need to be more concerned with equity than equality. Allen's needs are different than those of his siblings.

If everyone is equal, if everyone is ordinary. then the extraordinary is out of reach.

And each time I kick another piece of bird-shot across the living room, I will remember it. Allen is, in his own way, extraordinary.

Marvelous piece, Linda. I'm thankful we are not all the same, and equal in all ways. What a dull world that would be.

ReplyDelete