7/31/14

We are at

Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia for the second day of Ron’s ketamine

infusions and I am pretty much done the school work I have brought for the 5

hour wait. Now I am reading, knitting, and writing. The knitting is a shawl

begun last week at Bethany beach and is almost finished, the book is Marian

Cohen’s Dirty Details, and the writing is this, my ever-present journal

which sometimes transfers to my blog but may just as often stay trapped inside

the paper covers. An orange “CRPS” awareness bracelet –a gift from Danielle’s

mother this morning—is on my right wrist. I read some of Dani’s blog last

night, a cheerful account of her own battle with complex regional pain

syndrome. When I saw Dani yesterday, after her treatment, she was not so

cheerful but was in intense pain. On the way up in the elevator this morning,

Dani’s mother commented, “It is so hard to have an ill child.” I nodded in

agreement, knowing that having an ill spouse is no picnic either. As we exited

the elevator and steered our patients towards the infusion room, she asked me, “What

do people do who have no caregivers?”

No idea.

I do know that I

am, in this waiting room off of Broad Street, finding other Well Spouses—or well

parents—and benefitting from the shared experiences. Despite whatever initial

event –accident, surgery, stroke—brought them to this place, we all share a

hard-won knowledge: no one is coming to rescue us.

Most of us felt,

in the early days of our journey as well spouses or care-givers, that surely

this could not now be our lives! It had to be a cruel joke, this sudden thrust

of total responsibility for another’s care and feeding. Far different than

suddenly being sent home with a new baby to cuddle, the people we came home

from hospitals with were ill, sullen, demanding, and messy. There were no cute

smiles or gurgles, no playing “this little piggy” with feet often too painful

to wear shoes, no welcoming gifts in pink or blue paper.

“This cannot be

it!” we all thought. “Surely we will get help. Surely the—fill in the blank

here with universe, God, government, hospital, the good people at State Farm—will

not allow this sorry condition to continue.” So, at the beginning, we fulfilled

our given roles as caregivers as cheerfully as we could, convinced it would be

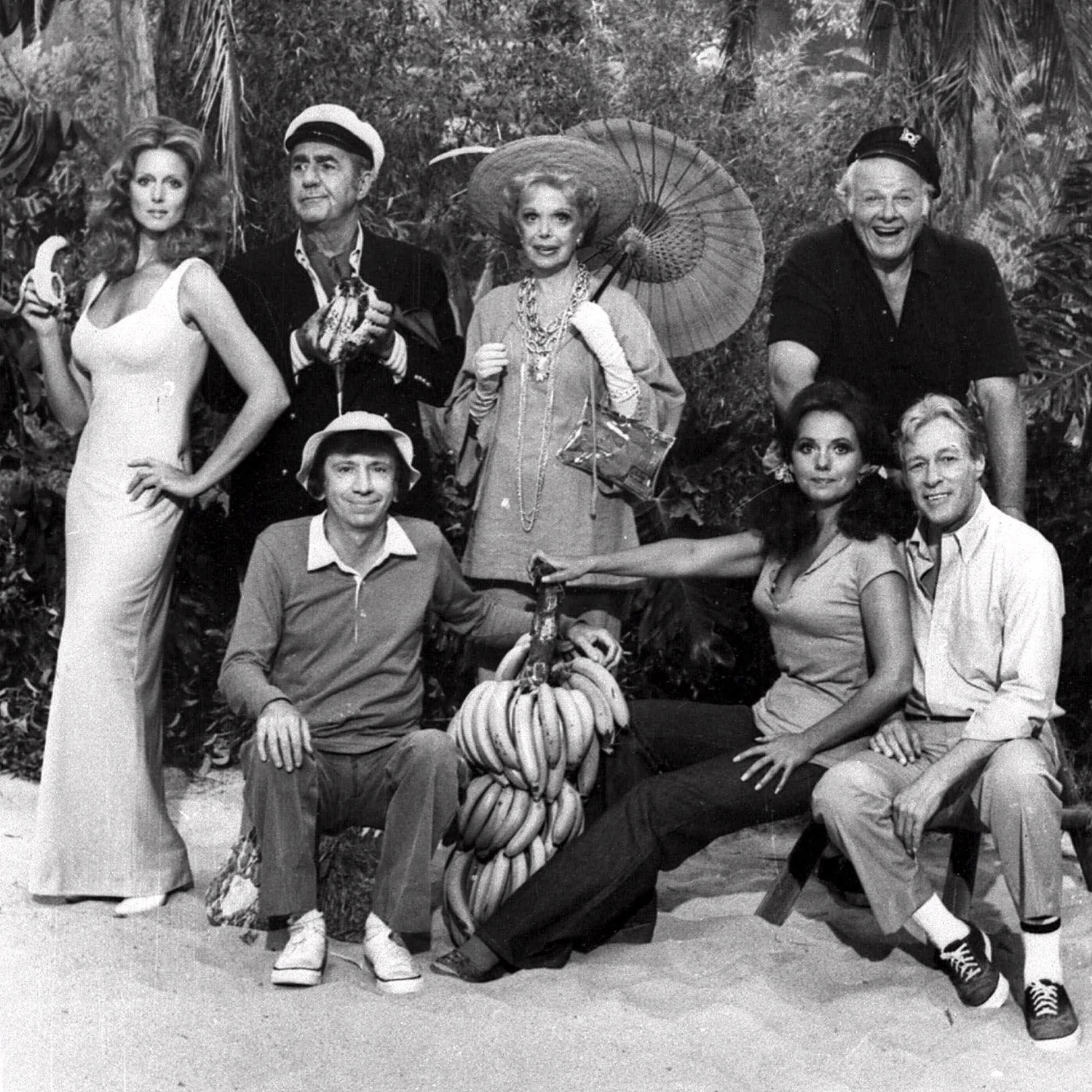

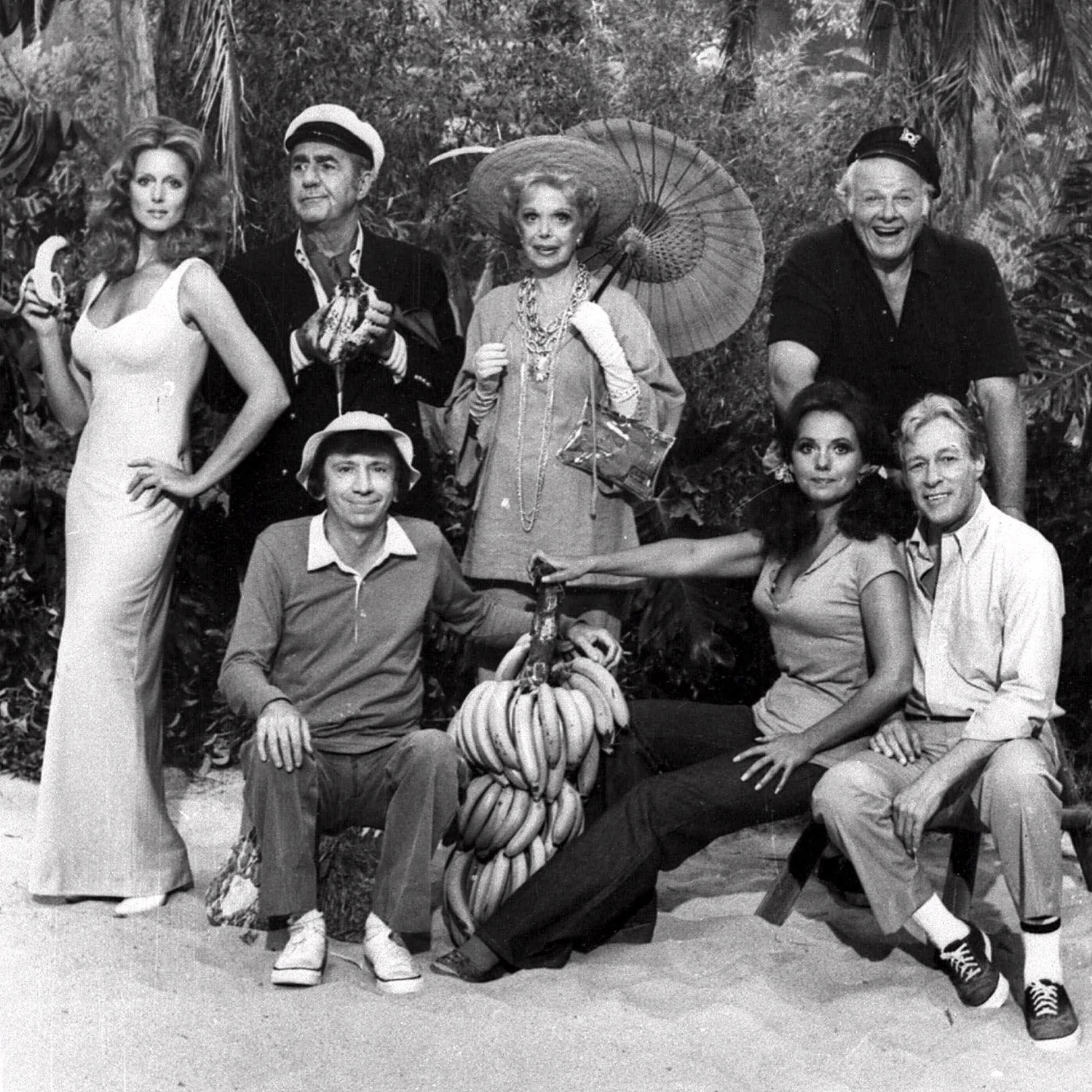

temporary. We would, sooner or later, be rescued. Like those castaways on

Gilligan’s Island, we lived in hope.

It was not so bad,

at the beginning. We got some help from friends and neighbors, people at work

or at church. They would stop by now and again, bringing a hot meal or offering

to do a load of laundry. It is what I came to think of as the “novelty phase.” Just

as new grandmas are eager to help out the exhausted new mother, people came.

But a chronic

illness does not go away. The well-meaning, good people with casserole dishes

go back to their own lives. “Call if you need help,” they say in parting. And

we caregivers nod, knowing that we will never make the call. There will be no

rescue.

Cohen, in Dirty

Details, admits to having tantrums when she realized that rescue would

never come. My method of dealing with it all was different: I accepted every

burden, every messy task, every indignity as my due. Retribution, perhaps, for some

forgotten sin. I suffered for years in a strained silence, waiting for rescue,

praying for rescue, but never asking.

I would pass

fellow teachers in the hallway and wonder why they did not see my Well Spouse

status and offer me—I don’t know—an out? An arm? A prayer? Something. Anything.

But Well Spouses

have what Cohen calls an “invisible disability.” When we are with our Ill

Spouses, helping them negotiate walkers down hallways, someone will open a door

or offer to carry a bag. But without our Ill Spouses by our sides, no one can

see our disability. We are still disabled, still working too many hours to

support a family that used to have two incomes, still going home to cook dinner

and change the catheter bag, relieve the day nurse, run the vacuum cleaner,

make a meal our Ill Spouses can digest, run endless loads of smelly laundry,

then collapse into a boneless heap after our Ill Spouses are settled for the

night, knowing that a solid night’s uninterrupted sleep is a myth.

If only, as Cohen

states, the would-be rescuers would not wait to be called but would offer substantive

help, such as, “I’m coming over on Thursday night to watch the game with Ron,

so take the evening off”, or “I’m headed to the market on Monday. Give me your

list”, or “I made two roasts last night and I am dropping one off.”

Some of these

things have happened from time to time and I have been grateful. I do not mean

to complain. But my Ill Spouse’s problem is not an appendectomy that will be

healed. Ron is, like so many, chronically ill and has been for fourteen years.

We deal with the after-effects of the accident—TBI, CRPS, COPD, atonic bladder,

depression—on a daily basis. We have come to accept them as members of the family,

here to stay.

Here is where I,

along with Cohen, make the impossible wish; all of you who are friends of the

long-suffering Well Spouse or Well Parent need to get together and work it out.

Not a once a year benefit to pay for out-of-pocket medical expenses—although it

would be nice if even one of Ron’s $225 ketamine treatments could be covered—but

on a permanent basis. Offer, say, to do the marketing once a month or

clean my

house every second Tuesday or visit Ron during the World Series. Take my Ill

Spouse to the barber every six weeks or maybe buy us dinner on a day with an “e”

in its name. Anything, as long as it is consistent and done willingly—not out

of guilt—without waiting for the Well Spouse to pick up the phone.

Because a woman or

man who works sixty hours a week at three jobs, who spends evenings doing housework and laundry and

caring for the Ill Spouse, who tries to squeeze in some church ministry, who

can only do any writing before the sun rises, is not going to pick up the phone

and call you. There is just no time.

So, like those castaways on

Gilligan’s Island, we know there will be no rescue. But we continue to look for

that search plane in the sky, the one that will finally and forever take us off

the Island of the Well Spouse.

I’ve made good on my promise.

Despite the hospital trips and the medical bills and all the things I need to

do as the Well Spouse, I think of myself foremost as writer and teacher, not

care giver. I recognize that I have

gained much these last fourteen years. Even if Ron were to be cured tomorrow,

there would be no going back.

I’ve made good on my promise.

Despite the hospital trips and the medical bills and all the things I need to

do as the Well Spouse, I think of myself foremost as writer and teacher, not

care giver. I recognize that I have

gained much these last fourteen years. Even if Ron were to be cured tomorrow,

there would be no going back.