I have explained the process of a cornea transplant to my son as carefully as I can, high-lighting the fact that the procedure will restore vision to my right eye and bypassing the rather queasy details. He nods. He sort of remembers from the last time, but he was little and his father was, unlike now, more able to take care of things.

I have explained the process of a cornea transplant to my son as carefully as I can, high-lighting the fact that the procedure will restore vision to my right eye and bypassing the rather queasy details. He nods. He sort of remembers from the last time, but he was little and his father was, unlike now, more able to take care of things.

This, his sister has told me, is Allen's biggest worry: that I will become as incapacitated as his disabled dad. I want him to know that after some recovery time I will be right as rain. No need to worry.

But worry he does. "What will help you feel better?" he asks me.

I talk about taking care of the cats and making sure I get hot tea when I need it, but he needs something much more solid. Like many on the autism spectrum, Allen is very concrete in his thinking. The fact that he is considering my feelings shows how far he has come in the last few years.

I talk about taking care of the cats and making sure I get hot tea when I need it, but he needs something much more solid. Like many on the autism spectrum, Allen is very concrete in his thinking. The fact that he is considering my feelings shows how far he has come in the last few years.

I think carefully. It needs to be something easily attained, but also related directly to my successful recovery.

"Slippers," I tell him. "Nice comfy slippers I can wear while I'm laying around and my eye heals."

"Slippers," I tell him. "Nice comfy slippers I can wear while I'm laying around and my eye heals."

"Fine,"he says. "I will get you slippers. Then you'll be okay."

I forget about it for a few days. There is much to be done to provide for Ron's needs as I am on the injured list for a while. Thursday night, Allen heads out the door. "Going to Walmart," he tells me. "I need to get you slippers." It has become a mission for him. Alas, when he returns an hour later he sadly reports that he couldn't find any. "Not nice ones," he says.

I want to tell him to forget it, but I know that the slippers are now tied up with his confidence that I will recover, so I simply say, "There are other stores." And on Friday, Allen heads out again in search of something I thought would be easy for him to find. But he still comes back empty-handed. Who knew slippers were such a commodity?

Saturday morning dawns. We are supposed to attend Wendy's Cancer Free Party and I awaken Allen at 10 am to remind him. I hear him get up and shower, then zoom down the steps and out the door. "We're leaving at 11:30!" I shout, but he is already racing towards his car. By the time my daughter Bonnie arrives to chauffeur us to Roxborough, Allen has not returned. Bonnie texts him but gets no response.

Saturday morning dawns. We are supposed to attend Wendy's Cancer Free Party and I awaken Allen at 10 am to remind him. I hear him get up and shower, then zoom down the steps and out the door. "We're leaving at 11:30!" I shout, but he is already racing towards his car. By the time my daughter Bonnie arrives to chauffeur us to Roxborough, Allen has not returned. Bonnie texts him but gets no response.

"He knew we were leaving, " I say. I write a note and attach it to the door. I am not really worried about him but I ask him to call us when he gets home. I'm just a little annoyed that he has forgotten about the party.

It is an hour later and we are helping Wendy set things up when Bonnie's phone dings with a text. She smiles and reads it to me.

FOUND MOM'S SLIPPERS. SHE'LL BE FINE NOW.

Any annoyance I had at my adult autistic son flies away. The slippers have become such an objective to him that nothing else matters.

Bonnie gives me a hug. "You have to get better now," she says. "Allen found you slippers!"

My magic slippers are packed and ready.

Dear Friend,

We've been together for almost twenty years, but on June 20, 2017, we will say good-bye forever. I will miss you more than I can possibly express; you have--quite literally--been a part of me. The years between our meeting and our parting have been chaotic. Your constant presence has not only helped me to survive, but to thrive. In addition, the very bestowal of you has allowed me to care for my family and raise my children, to provide for my disabled husband, and to impart the gift of knowledge to many students and teachers. I am beyond grateful for you.

We've been together for almost twenty years, but on June 20, 2017, we will say good-bye forever. I will miss you more than I can possibly express; you have--quite literally--been a part of me. The years between our meeting and our parting have been chaotic. Your constant presence has not only helped me to survive, but to thrive. In addition, the very bestowal of you has allowed me to care for my family and raise my children, to provide for my disabled husband, and to impart the gift of knowledge to many students and teachers. I am beyond grateful for you.

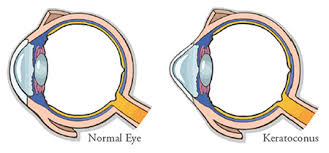

Our close relationship began on February 14, 1998--a most appropriate date--when a surgeon at Wills' Eye Hospital in Philadelphia removed your damaged predecessor from my right eye. A corneal dystrophy called keratoconus had destroyed it and all efforts to save it had come to naught. You, my dear right cornea, were affixed to a narrow circle of tissue with 120 tiny sutures. I came home from the hospital with a bandage over you, a throbbing headache, and a hope that you might provide me with the gift of sight.

And you did. It took a while for vision of any sort to return; I spent two months with slowly increasing visual acuity.

And you did. It took a while for vision of any sort to return; I spent two months with slowly increasing visual acuity.

It took even longer for me to feel that you were truly mine, not a foreigner to my body. For half a year, every blink dragged down over sutures that broke painfully or were removed at the hospital. Even after the last suture was gone, the vague feeling remained that you did not really belong.

Gradually, the early morning notion that there was "something in my eye" dissipated. You became mine.

For a while, you could tolerate the rigid gas permeable lens and my vision was a pretty miraculous 20/60. It was enough to teach high school English and earn a graduate degree in Reading. And when my husband, Ron, was in a car accident that nearly took his life, you stayed firmly affixed to my eye as we took on two and three jobs to support the family.

For a while, you could tolerate the rigid gas permeable lens and my vision was a pretty miraculous 20/60. It was enough to teach high school English and earn a graduate degree in Reading. And when my husband, Ron, was in a car accident that nearly took his life, you stayed firmly affixed to my eye as we took on two and three jobs to support the family.

By the time we had been together ten years--the usual life of a donor cornea--we were firmly implanted into a doctoral program and you were showing signs of wear. You would no longer wear the RGP with any degree of comfort so we switched back to our thick glasses and moved on. My life was too hectic to deal with the routine of contact lenses anyway, what with caring for Ron and teaching at three colleges.

We made it, you and I. I saw--if through a haze--all three offspring graduate college. I received my doctorate in 2011. I knitted my way through Ron's various surgeries and saw well enough to help my daughter make her wedding gown.

We made it, you and I. I saw--if through a haze--all three offspring graduate college. I received my doctorate in 2011. I knitted my way through Ron's various surgeries and saw well enough to help my daughter make her wedding gown.

Around 2015, you began to protest. The ghost images from you were now full-blown doubles and I had trouble with stairs and certain colors. I could only read on my Kindle set to a large print font. My good friend Dr. Neil Schwartz declared you to be "clinically blind."

I lived with it for a while, depending heavily on my still good left eye. But in March of 2016, I woke up one morning to a heavy fog that would not lift. I went to Neil, who referred me to a cornea specialist. She sent me to be fitted for a hybrid lens, but that ophthalmologist said you were too far gone. I saw another specialist, who referred me to a retina specialist, who referred me to a neuro-ophthalmologist, who referred me back to Wills'.

I lived with it for a while, depending heavily on my still good left eye. But in March of 2016, I woke up one morning to a heavy fog that would not lift. I went to Neil, who referred me to a cornea specialist. She sent me to be fitted for a hybrid lens, but that ophthalmologist said you were too far gone. I saw another specialist, who referred me to a retina specialist, who referred me to a neuro-ophthalmologist, who referred me back to Wills'.

Where we first met. We have come full circle, dear friend.

And as I prepare for the surgery and the recovery time I will need once you are removed from my eye and another donor cornea takes your place, I want to thank you for all you have allowed me to do. Someone somewhere gave me a very precious gift when they donated their corneas to be used for people like me. In saying "thanks" to you, I am really saying it to that nameless person who not only gave me the gift of sight, but the gift of life.

On June 20, I begin the journey again with a new cornea, a new chance to see and to live and to make meaning from my life. It is a charge I will never take for granted.

So thanks, dear friend. I will never forget you. I pray that I have been, and will continue to be, worthy of such a rare and wonderful gift.

With great gratitude,

Linda

P.S. Dear readers, if you have not already done so, please consider giving others such as myself the gift of sight by donating your corneas after death. The Eye Bank Association of American can help you understand the process.

http://restoresight.org/cornea-donation/understanding-cornea-donation/