Some times it takes a while for things to sink in. Last Sunday, a student at college, after hearing about Ron's recent illnesses and continuing hospitalization, says this to me: "You must really love him." I am busy at the moment--I am always busy--so I tuck the comment away for later mulling. Like many tiny seeds, it settles in and begins to grow.

When I, at the knowledgeable age of 20, married Ron almost 40 years ago, I suspected that his love for me was greater than my love for him. It worried me, what I saw as an imbalance, so I did everything I could to be the best wife possible. I saw love, lo those many years ago, as a finite quality. You had only so much to give and you weren't getting anymore. The births of my three children showed me that love could be all-encompassing. So much was my love for my children, I feared I would have none left for my husband.

I need not have worried. What I did not know at the beginning of our marriage, I began to discover after the first twenty years.

Love grows. It grows deep.

It is not, I hasten to say, the love advertised in sappy Hallmark cards or in Harlequin romance novels. Real love, deep love, love meant to last a lifetime, grows through trials and triumphs, joys and sorrows, gains and losses. The birth of our first son, Dennis, was a gain. The loss of our second child was not. And so it went on, tallies being put into a ledger sheet of negatives and positives, more or less evening out. If not the stuff of fairy tale endings, it was still a good life. I was content.

Chronic depression first came to live with us in 1995, putting our marriage vows to the test. Ron's personality changed as mood swings took over. I struggled, at times, to recognize in him the man I had married. I thought about leaving him--more than once--but I still hoped and prayed we would find our way out of the maze. During his calm periods, there was enough left of Ron to convince me that he still dwelled inside. I stayed. We managed. But as more and more of my husband's self was given over to his fight against unseen forces, I found myself growing in strength, and courage, and faith.

More positives to the ledger.

People--well-meaning, I am sure--asked me why I stayed. My answer was, I thought, a reasonable one. I stayed because my marriage vows had meant something to me. I stayed out of duty and commitment. I assumed, without really examining it, that it was also out of love.

We were already pretty heavy on the negative side of the balance sheet when the infamous red pickup truck struck and all but killed Ron. We'd survived--by the skin of our teeth, I might add--a lengthy hospitalization at Friends' the summer before and I was hoping for a little calm in my way too hectic life. Fast forward over the last 15 years to many hospitalizations and surgeries and we arrive at last Sunday and my student's words, still working their way into my brain.

"You must really love him."

My 20 year old self, wearing the white veil and saying "I do" couldn't possibly have known this, but life and love are not a balance sheet. Love, when allowed, takes root and grows. It starts with that tiny seed--the quickened pulse, the slightly dizzy feeling when near the loved one--and it takes root in our soul. It is watered by both tears and joys. It becomes a part of you. It became a part of me.

Acquaintances, both old and new, always express astonishment at what our family has been through and particularly at how I have managed to hold so many things together and still maintain a positive attitude. Yesterday, on the way home from visiting Ron in his current hospital, I asked my daughter why this is. Do people think I've lost my own marbles because I continue to do this? Have I , indeed, gone around the bend myself?

She smiled at me. "They think, Mom," she said, "that you are the most amazing woman they have ever met. They think that they couldn't do what you have done." She hugged me. "And you don't even know how amazing you are."

I cannot claim to always be amazing, because it is hard to have a husband who has been so ill and continues to require much care. But Ron has become so much a part of my life and my spirit, that the word "love" does not come close to expressing what I feel. It is, I hope, what God intended love to be when He saw that lonely Adam needed a help-mate in the Garden of Eden. My choice to continue with Ron also means I make the choice to continue growing and allowing the love of both my husband and God to take root in me. I recognize that others might not be able to do what I have done. I do not judge. I do what I need to do and, in same ways, I do it for me as much as for Ron. Love has been planted in my soul.

A while back, an acquaintance of mine said that she would like to "be me when she grew up." I reminded her that my life was far from easy. "I know," she said wistfully. "It's not your life I admire. It's the grace with which you live it."

I quit keeping track of the balance sheet long ago. A life cannot be measured by positives and negatives. While years ago, I considered myself to be content with life, I now know that I have come to a better state. Despite being mostly tired and sometimes discouraged and often upbeat, I have joy that does not depend upon outward trappings.

Soul deep joy. Soul deep love.

So, does anyone else want to be me when they grow up?

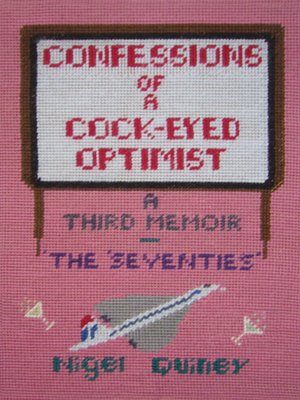

I’m pretty sure that I’ve always

been a optimist, whether because of the incessant lyrics of dear Nurse Nellie

or a hereditary propensity towards the positive. My father himself is of such a

cheerful nature that colleagues at Westinghouse Electric nicknamed him “Harvey

Smilingsdorf.” There’s just something in my genes that helped me survive Ron’s

accident and aftermath, that still lets me look ahead to a brighter future

despite being dog-tired. But it’s not just pie-in-the-sky, rose-colored

glasses, and out-of-touch-with-reality optimism. Hey, I KNOW the worst can

happen. I also know it can be survived.

I’m pretty sure that I’ve always

been a optimist, whether because of the incessant lyrics of dear Nurse Nellie

or a hereditary propensity towards the positive. My father himself is of such a

cheerful nature that colleagues at Westinghouse Electric nicknamed him “Harvey

Smilingsdorf.” There’s just something in my genes that helped me survive Ron’s

accident and aftermath, that still lets me look ahead to a brighter future

despite being dog-tired. But it’s not just pie-in-the-sky, rose-colored

glasses, and out-of-touch-with-reality optimism. Hey, I KNOW the worst can

happen. I also know it can be survived.